Private Cloud Posts Should Come in Threes

Over the last year I have returned to the subject of ‘private cloud’ on a number of occasions. Basically I’m trying to share my confusion as I still don’t really ‘get it’.

First of all I discussed some of the common concerns related to cloud that are used to justify a pursuit of ‘private cloud’ models. In particular I tried to explain why most of these issues distract us from the actual opportunities; for me cloud has always been a driver to rethink the purpose and scope of your business. In this context I tried to explain why – as a result – public and private clouds are not even vaguely equivalent.

More recently I mused on whether the whole idea of private clouds could lead to the extinction of many businesses who invest heavily in them. Again, my interest was on whether losing the ability to cede most of your business capabilities to partners due to over-investment in large scale private infrastructures could be harmful. Perhaps ‘cloud-in-a-box’ needs a government health warning like tobacco.

In this third post I’d like to consider the business case of private cloud to see whether the concept is sufficiently compelling to overcome my other objections.

A Reiteration of My View of Cloud

Before I start I just wanted to reiterate the way I think about the opportunities of cloud as I’m pretty fed up of conversations about infrastructure, virtualisation and ‘hybrid stuff’. To be honest I think the increase in pointless dialogue at this level has depressed my blog muse and rendered me mute for a while – while I don’t think hypervisors have anything to do with cloud and don’t believe there’s any long term value in so called ‘cloud bursting’ of infrastructure (as an apparently particularly exciting subject in my circle) I’m currently over-run by weight of numbers.

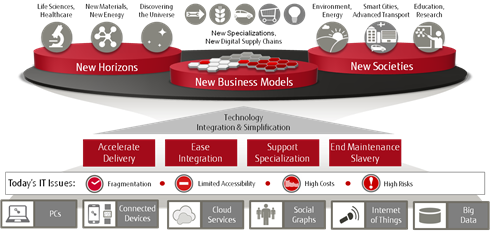

Essentially its easy to disappear down these technology rat holes but for me they all miss the fundamental point. Cloud isn’t a technology disruption (although it is certainly disrupting the business models of technology companies) but eventually a powerful business disruption. The cloud enables – and will eventually force – powerful new business models and business architectures.

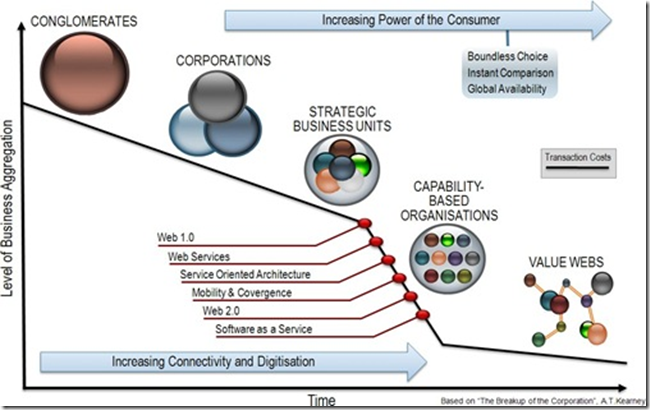

As a result cloud isn’t about technology or computing per se for me but rather about the way in which technology is changing the economics of working with others. Cloud is the latest in a line of related technologies that have been driving down the transaction costs of doing business with 3rd parties. To me cloud represents the integration, commoditisation and consumerisation of these technologies and a fundamental change in the economics of IT and the businesses that depend on it. I discussed these issues a few years ago using the picture below.

Essentially as collaboration costs move closer and closer to zero so the shape of businesses will change to take advantage of better capabilities and lower costs. Many of the business capabilities that organisations currently execute will be ceded to others given that doing so will significantly raise the quality and focus of their own capabilities. At the same time the rest will be scaled massively as they take advantage of the ability to exist in a broader ecosystem. Business model experimentation will become widespread as the costs of start up (and failure) become tiny and tied to the value created. Cloud is a key part of enabling these wider shifts by providing the business platforms required to specialise without losing scale and to serve many partners without sacrificing service standardisation. While we are seeing the start of this process through offerings such as infrastructure-as-a-service and software-as-a-service these are just the tip of the iceberg. As a very prosaic example many businesses are now working hard to think about how they can extend their reach using business APIs; combine this with improving business architecture practices and the inherent multi-tenancy of the cloud and it is not difficult to imagine a future in which businesses first become a set of internal service providers and then go on to take advantage of the disaggregation opportunity. In future, businesses will become more specialised, more disaggregated and more connected components within complex value webs. Essentially every discrete step in a value stream could be fulfilled by a different specialised service provider, with no ‘single organisation’ owning a large percentage of the capabilities being coordinated (as they do today).

As a result of all of these forces my first statement is therefore always that ‘private cloud’ does not really exist; sharing some of the point technologies of early stage cloud platform providers (but at lower scale and without the rapid learning opportunities they have) is not the same as aggressively looking to leverage the fall in transaction costs and availability of new delivery models to radically optimise your business. Owning your own IT is not really a lever in unlocking the value of a business service based ecosystem but rather represents wasteful expense when the economics of IT have shifted decisively from those based on ownership to those based on access. IT platforms are now independent economy-of-scale based businesses and not something that needs to be built, managed and supported on a business-by-business basis with all of the waste, diversity, delay and cost that this entails. Whilst I would never condemn those who have the opportunity to improve their existing estates to generate value I would not accept that investing in internal enhancement would ever truly give you the benefits of cloud. For this reason I have always disliked the term ‘private cloud’.

In the light of this view of the opportunities of cloud, I would posit that business cases for private cloud could be regarded as lacking some sense even before we look at their merit. Putting aside the business issues for a moment, however, let’s look at the case from the perspective of technology and how likely it is that you will be able to replicate the above benefits by internal implementation.

What Is a “Cloud”?

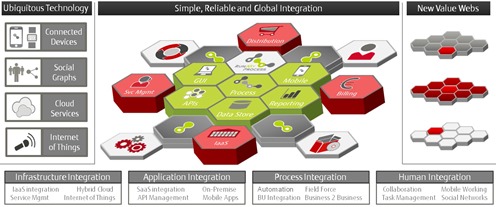

One of the confusing issues related to cloud is that it is a broad shift in the value proposition of IT and IT enabled services and not a single thing. It is a complete realignment of the IT industry and by extension the shape of all industries that use it. I have a deeper model I don’t want to get into here but essentially we could view cloud as a collection of different kinds of independent businesses, each with their own maturity models:

- Platforms: Along the platform dimension we see increasing complexity and maturity going –> infrastructure-as-a-service, platform-as-a-service, process-platform-as-a-service through to the kind of holistic service delivery platform I blogged about some time ago. These are all increasingly mature platform value propositions based on technology commoditisation and economies of scale;

- Services: Along the services dimension we see increasing complexity and maturity going –> ASP (single tenant applications in IaaS), software-as-a-service, business-processes-as-a-service through to complete business capabilities offered as a service. While different services may have different economic models, from a cloud perspective they share the trait that they are essentially about codifying, capturing and delivering specialised IP as a multi-tenant cloud service; and

- Consulting: Along the consulting dimension we see increasing complexity and maturity going –> IT integration and management, cloud application integration and management, business process integration and management through to complex business value web integration and management. These all exist in the same dimension as they are essentially relationship based services rather than asset based ones.

All of these are independent cloud business types that need to be run and optimised differently. From a private cloud perspective, however, most people only think about the ‘platform’ case (i.e. only about technology) and think no further than the lowest level of maturity (i.e. IaaS) – even though consulting and integration is actually the most likely business type available for IT departments to transition to (something I alluded to here). In fact its probably an exaggeration to say that people think about IaaS as most people don’t get beyond virtualisation technology.

Looking at services – which is what businesses are actually interested in, surprisingly – this is probably the biggest of the many elephants in the room with respect to private cloud; if the cloud is about being able to specialise and leverage shared business services from others (whether applications, business process definitions or actual business capabilities) then they – by definition – execute somewhere beyond the walls of the existing organisation (i.e. at the service provider). So how do these fit with private cloud? Will you restrict your business to only ever running the old and traditional single-tenant applications you already have? Will you build a private cloud that has a flavour of every single platform used or operated by specialised service providers? Will you restrict your business to service providers who are “compatible” with your “platform” irrespective of the business suitability of the service? Or do you expect every service provider to rewrite their services to run on your superior cloud but still charge you the same for a bespoke service as they charge for their public service? Whichever one you pick it’s probably going to result in some pain and so you might want to think about it.

Again, for the sake of continuing the journey let’s ignore the issue of services – as it’s an aspect of the business ecosystem problem we’ve already decided we need to ignore to make progress – and concentrate where most people stop thinking. Let’s have a look at cloud platforms.

Your New Cloud Platform

The first thing to realise is that public cloud platforms are large scale, integrated, automated, optimised and social offerings organised by value to wrap up complex hardware, networks, middleware, development tooling, software, security, provisioning, monetisation, reporting, catalogues, operations, staff, geographies etc etc and deliver them as an apparently simple service. I’ll say it again – cloud is not just some virtualisation software. I don’t know why but I just don’t seem able to say that enough. For some reason people just underestimate all this stuff – they only seem to think about the hypervisor and forget the rest of the complexity that actually takes a hypervisor and a thousand other components and turns them into a well-oiled, automated, highly reliable and cross functional service business operated by trained and motivated staff.

Looking at the companies that have really built and operated such platforms on the internet we can see that there are not a large number due to:

- The breadth of cross functional expertise required to package and operate a mass of technologies coherently as a cost-effective and integrated service;

- The scarcity of talent with the breadth of vision and understanding required to deliver such an holistic offering; and

- The prohibitive capital investment involved in doing so.

Equally importantly these issues all become increasingly pressing as the scope of the value delivered progesses up the platform maturity scale beyond infrastructure and up to the kind of platform required for the realisation and support of complete multi-tenant business capabilities we described at the beginning.

Looking at the companies who are building public cloud platforms it’s unsurprising that they are not enthusiastically embracing the nightmare of scaling down, repackaging, delivering and then offering support for many on-premise installations of their complex platforms across multiple underfunded IT organisations for no appreciable value. Rather they are choosing to specialise on delivering these platforms as service offerings to fully optimise the economic model for both themselves and (ironically) their customers.

Whereforeart Thou Private Cloud?

Without the productised expertise of organisations who have delivered a cloud platform, however, who will build your ‘private cloud’? Ask yourself how they have the knowledge to do so if they haven’t actually implemented and operated all of the complex components as a unified service at high scale and low cost? Without ‘productised platforms’ built from the ground up to operate with the levels of integration, automation and cost-effectiveness required by the public cloud, most ‘private cloud’ initiatives will just be harried, underfunded and incapable IT organisations trying to build bespoke virtualised infrastructures with old, disparate and disconnected products along with traditional consulting, systems integration and managed services support. Despite enthusiastic ‘cloud washing’ by traditional providers in these spaces such individual combinations of traditional products and practices are not cloud, will probably cost a lot of money to build and support and will likely never be finished before the IT department is marginalised by the business for still delivering uncompetitive services.

Trying to blindly build a ‘cloud’ from the ground up with traditional products, the small number of use cases visible internally and a lack of cross functional expertise and talent – probably with some consulting and systems integration thrown in for good measure to help you on your way – could be considered to sound a little like an expensive, open ended and high risk proposition with the potential to result in a white elephant. And this is before you concede that it won’t be the only thing you’re doing at the time given that you also have a legacy estate to run and enhance.

Furthermore, go into most IT shops and check out how current most of their hardware and software is and how quickly they are innovating their platforms, processes and roles. Ask yourself how much time, money and commitment a business invests in enabling its _internal IT department_ to pursue thought leadership, standards efforts and open source projects. Even once the white elephant lands what’s the likelihood that it will keep pace with specialised cloud platform providers who are constantly improving their shared service as part of their value proposition?

For Whom (does) Your Cloud (set its) Tolls?

Once you have your private cloud budget who will you build it for? As we discussed at the outset your business will be increasingly ceding business capabilities to specialised partners in order to concentrate on their own differentiating capabilities. This disaggregation will likely occur along economic lines as I discussed in a previous post, as different business capabilities in your organisation will be looking for different things from their IT provision based on their underlying business model. Some capabilities will need to be highly adaptable, some highly scalable, some highly secure and some highly cost effective. While the diversity of the public cloud market will enable different business capabilities within an organisation to choose different platforms and services without sacrificing the benefits of scale, any private cloud will necessarily be conflicted by a wide diversity of needs and therefore probably not be optimal for any. Most importantly every part of the organisation will probably end up paying for the gold-plated infrastructure required by a subset of the business and which is then forced onto everyone as the ‘standard’ for internal efficiency reasons.

You therefore have to ask yourself:

- Is it _really_ true that all of your organisation’s business capabilities _really_ need private hosting given their business model and assets? I suspect not;

- How will you support all of the many individual service levels and costs required to match the economics of your business’s divergent capabilities? I suspect you can’t and will deliver a mostly inappropriate ‘one size fits all’ platform geared to the most demanding use cases; and

- How will you make your private infrastructure cost-effective once the majority of capabilities have been outsourced to partners? The answer is that you probably won’t need to worry about it – I suspect you’ll be out of a job by then after driving the business to bypass your expensive IT provision and go directly to the cloud.

Have We Got Sign-off Yet?

So let’s recap:

- Private cloud misses the point of the most important disruption related to cloud – that is the opportunity to specialise and participate more fully in valuable new economic ecosystems;

- Private cloud ignores the fundamental fact that cloud is a ‘service-oriented’ phenomenon – that is the benefits are gained by consuming things, uh as a service;

- Private cloud implementation represents a distraction from that part of the new IT value chain where IT departments have the most value to add – that is as business-savvy consultants, integrators and managers of services on behalf of their business.

To be fair, however, I will take all of that value destruction off the table given that most people don’t seem to have got there yet.

So let’s recap again just on the platform bit. It’s certainly the case that internal initiatives targeted at building a ‘private cloud’ are embarking on a hugely complex and multi-disciplinary bespoke platform build wholly unrelated to the core business of the organisation. Furthermore given that it is an increasing imperative that any business platform supports the secure exposure of an organisation’s business capabilities to the internet they must do this in new ways that are highly secure, standards based, multi-tenant and elastic. In the context of the above discussion, it could perhaps be suggested that many organisations are therefore attempting to build bespoke ‘clouds’:

- Without proven and packaged expertise;

- Without the budget focus that public cloud companies need merely to stay in business;

- Often lacking both the necessary skills and the capability to recruit them;

- Under the constant distraction of wider day to day development and operational demands;

- Without support from their business for the activities required to support ongoing innovation and development;

- Without a clear strategy for providing multiple levels of service and cost that are aligned to the different business models in play within the company.

In addition whatever you build will be bespoke to you in many technological, operational and business ways as you pick best of breed ‘bits’, integrate them together using your organisations existing standards and create operational procedures that fit into the way your IT organisation works today (as you have to integrate the ‘new ops’ with the ‘old ops’ to be ‘efficient’). As a result good luck with ever upgrading the whole thing given its patchwork nature and the ‘technical differentiation’ you’ve proudly built in order to realise a worse service than you could have had from a specialised platform provider with no time or cost commitment.

Oh and the costs to operate whatever eventually comes out the other end of the adventure – according to Microsoft at least – could potentially be anywhere between 10 and 80 times higher than those you could get externally right now (and that’s on the tenuous assumption that you get it right first time over the next few years and realise the maximum achievable internal savings – as you usually do no doubt). To rephrase this we could say that it’s a plan to delay already available benefits for at least three years, possibly for longer if you mess up the first attempt.

I may be in the minority but I’m _still_ not convinced by the business case.

So What Should I Get Sign-off For?

My recommendation would be to just stop already.

And then consider that you are probably not a platform company but rather a consultant and integrator of services that helps your business be better.

So, my advice would be to:

- Stop (please) thinking (or at least talking) about hypervisors, virtual machines, ‘hybrid clouds’ and ‘cloud bursting’ and realise that there is inherently no business value in infrastructure in and of itself. Think of IaaS as a tax on delivering value outcomes and try not to let it distract you as people look to make it more complex for no reason (public/private/hybrid/cross hypervisor/VM management/cloud bursting/etc). It generates so much mental effort for so little business value;

- Optimise what you already have in house with whatever traditional technologies you think will help – including virtualisation – if there is a solid _short return_ business case for it but do not brand this as ‘private cloud’ and use it to attempt to fend off the public cloud;

- Model all of your business capabilities and understand the information they manage and the apps that help manage it. Classify these business capabilities by some appropriate criteria such as criticality, data sensitivity, connectedness etc. Effectively use Business Architecture to study the structure and characteristics of your business and its capabilities;

- Develop a staged roadmap to re-procure (via SaaS), redevelop (on PaaS) or redeploy (to IaaS) 80% of apps within the public cloud. Do this based on the security and risk characteristics of each capability (or even better replace entire business capabilities with external services provided by specialised partners); and

- Pressure cloud providers to address any lingering issues during this period to pave the way for the remaining 20% (with more sensitive characteristics) in a few years.

Once you’ve arrived at 5) it may even be that a viable ‘private cloud’ model has emerged based on small scale and local deployments of ‘shrink wrapped boxes’ managed remotely by the cloud provider at some more reasonable level above infrastructure. Even if this turns out to be the case at least you won’t have spent a fortune creating an unsupportable white elephant scaled to support the 80% of IT and business that has already left the building.

Whatever you do, though, try to get people to stop telling me that cloud is about infrastructure (and in particular your choice of hypervisor). I’d be genuinely grateful.